In my last castle post I said I’d talk about how England’s main castle custodian, English Heritage, actually works. Here we are! Enjoy!

The UK government has been looking after ‘important’ ruins for a very long time. The National Trust, for instance, is Europe’s largest conservationist charity and it was founded in the 1800s. But we aren’t gonna be talking about the National Trust here. Because although I respect them as a historian, my interests are a lot more… castley.

No, we’re going to be talking about English Heritage.

The History

English Heritage has a history even longer than the National Trust’s, though it was known by a different name back then.

The British government started caring for ‘nationally important’ monuments in the 1880s under the Office of Works. These powers grew after a 1913 Act of Parliament and by the 1930s the state was managing 273 historic sites, including Stonehenge. The familiar modern system was already apparent: these sites were open to the public, had staff to maintain them, were accompanied by guidebooks – many even had gift shops. This collection of sites became known as the National Heritage Collection (this is important, I’ll explain why in a bit), and by the 80s had grown even further, to over 300 sites.

Now, whenever Margaret Thatcher’s government is mentioned, it’s usually because it was tearing things down. But it was her ministry that looked at the size of the National Heritage Collection and decided it needed a whole government body of its own to manage it – so they set up the Historic Buildings and Monuments Commission.

This obviously wasn’t a very catchy name, and it wasn’t long before its first chairman, Lord Montagu, changed the name to the much more memorable English Heritage.

The new government body went from strength to strength, acquiring dozens of new sites and also setting up the system of listed buildings that we use today to protect important buildings that haven’t fallen into ruin – essentially by restricting what their owners can do to them. (If you’ve ever heard someone mention a Grade-II or Grade-I listed building, this is what they’re talking about.) Through prudent management, including setting up a membership system whereby people could pay once and be able to access all sites for free, English Heritage grew in popularity and in the amount of money it was making. In 2011, English Heritage sites were visited by 11.5 million people – and for the first time in its history, it made a surplus.

That’s right. A government-owned network of essentially-museums actually turned a profit. Which just goes to show that state funding of the arts doesn’t always have to be a huge money sink, as it’s often stereotyped as. But it does have to be run correctly.

The Change

Now I’m a massive fan of the ‘if it isn’t broke, don’t fix it’ school of philosophy. So when the British government announced in 2015 that it was planning to turn English Heritage into a private charity and slowly stop all government funding, I was… sceptical, to say the least. This was a rare example of a very big, very elaborate state-run museum system that actually wasn’t losing money. Why would you change it?! Anything could go wrong! And if it failed, what would happen to all those historic sites? Would the government actually buy them all back again?

But to my surprise, here we are five years later… and The English Heritage Trust is making a profit. And the buildings and listing system are both safe and in no danger.

I am pleasantly surprised by how well the whole thing has gone, which seems to be an increasingly foreign emotion these days. So I thought I’d delve into the details a bit and explain how this very castley success story actually happened.

Luckily for me, English Heritage releases its annual reports for the general public to read, so it hasn’t taken much digging. You can find them here if you fancy a look yourself.

How It Works Now

First: bestill your history heart, because the castles are safe. They were very clever and when they turned English Heritage into a charity, they also made a new government body called Historic England. This is the first example of how the charity is private but also not: The National Heritage Collection – the proper name for all English Heritage’s 410 sites – is still owned by Historic England, but the maintenance of the sites is handed over to EH. So if the charity ever folded, they would remain in the government’s hands. Phew.

Furthermore, all the trustees of the charity – the people who run it – are chosen by Historic England and at least half of them are members of it. So the government’s history body still basically runs the charity behind the scenes, so there’s no realistic chance of it being folded or exploited for individual profit.

So why did they make it a charity in the first place? In short, they wanted to be able to accept more public donations, expand their membership system and all-round diversify their sources of income to make English Heritage more stable in the long term. As a part of the government its ability to raise funds from the public was understandably quite restricted, and a charitable trust has many more options open to it.

The government also made sure to give it the best possible start they could: an £80million grant in the first year to make up for the initial shortfall as they switched to a different system, then a smaller grant every year afterwards until 2022, when it will be entirely self-funded.

What Do The Charts Say?

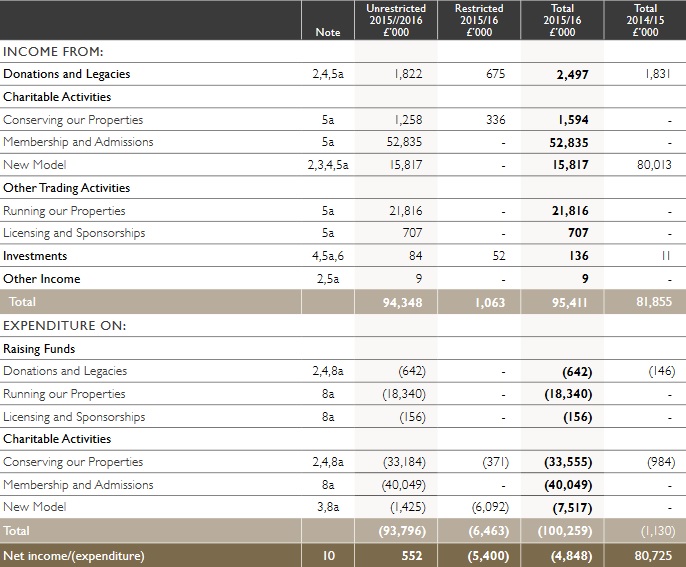

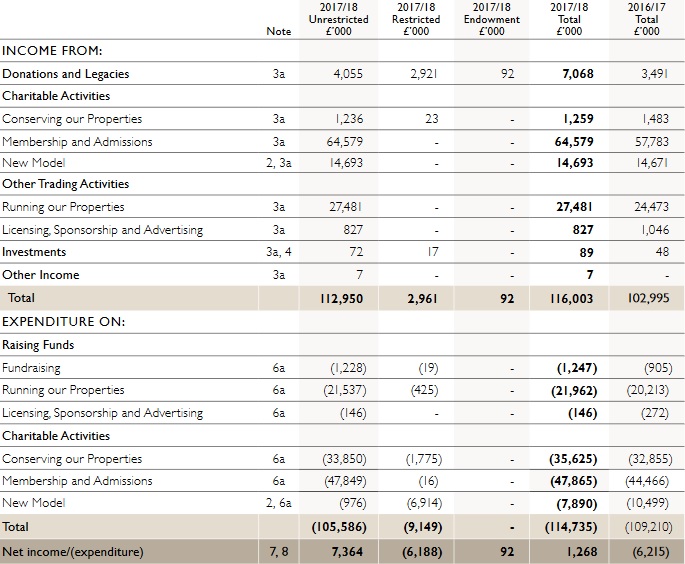

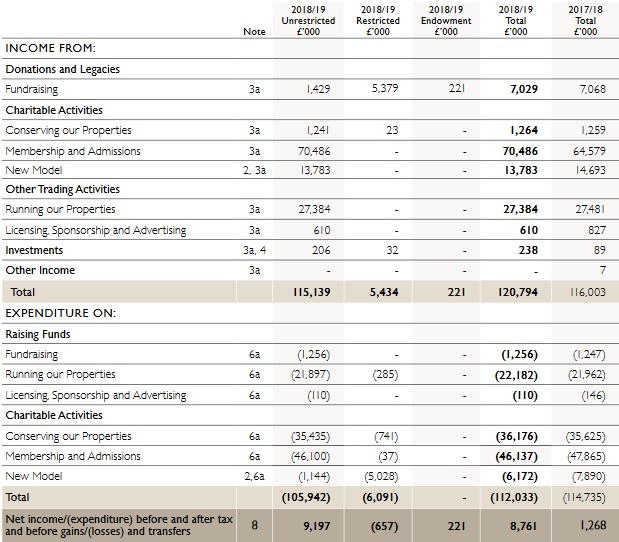

But how well has it worked so far? As I’m writing this, they’ve put out their annual reports for 2015-16, 2016-17, 2017-18 and 2018-19. So let’s have a look at their financial statements.

Here we have the statements for each of those years! Don’t be scared by all the numbers: the most important number is at the very bottom of the “Total [year]” column. These figures:

- 2015/16: £4,848,000 loss

- 2016/17: £6,215,000 loss

- 2017/18: £1,268,000 surplus

- 2018/19: £8,761,000 surplus

In other words, they’ve gone from losing £4million a year to making £8million in four years. There are a couple of caveats: they are still depending on that annual grant of government money (£16million in 2015, down to £14million in 2018), and they now have Brexit and the Corona crash coming up which might derail things, but the progress made so far? Very good. They’ve increased their membership by over 200,000 and now have over a million, which is where they’re getting most of their money from.

How have they turned the money around? Let’s have a look at the charts in more detail.

- The vast majority comes from “Membership and Admissions”. This made them £52.8million in 2015/16 and £70.5million in 2018/19.

- Income from “Donations and Legacies” went from £2.5million to £7million. This was because of an increasingly organised fundraising campaign – which was one of the main reasons for the switch from government body to private charity.

- “Running Our Properties” went from £21.8million to £27.4million – presumably through more trading or higher prices on their sites.

Interestingly, you’d expect them to have reduced their expenditure, but it’s actually gone up by £12million since 2015. That and the £52million grant they received have meant their sites have been maintained just as well as they ever were – in fact, the grant allowed them to do some large-scale repairs they’d needed to do for a long time. I saw this on the ground at Clifford’s Tower in York, a beautiful remnant of York Castle which English Heritage is going to do substantial work on in the next few years – planning permission for their project was submitted to the council in February 2020.

The Future

How’s it going to look going forward? I think 2020/21 will be an especially telling report, since by then we’ll be able to see if the economic effects of the virus and Brexit have had an impact. The government aims to have English Heritage entirely self-funded by 2022, but I don’t think that’ll happen now. My gut says it’ll take a couple years longer than that. But English Heritage have trumped the expectations of many in the history world so far, and they may yet continue to do so.

After all, they’ve beaten their financial projections in each of the four years so far: in 2018-19 they made £120mill in income, compared to an expected £110mill, and had an expenditure of £107mill over an expected £100mill.

They hit or came very close to the majority of the targets they set themselves in 2016, but one glaring fault is apparent: they expected to raise £30million through fundraising but only managed £22million, a fact they chalked up to the ‘challenging economic environment’. With all the crap that 2020 has thrown at us so far, I doubt this will have changed for the better. But I’m still hopeful.

Thanks for reading this far if you have. Times are tough and bad news is everywhere. But there are still some success stories, and some of them are pretty big. Like this one. If English Heritage manages this transition, it’ll be greater than ever before – and history in the UK will be better for it.

(I should probably go and renew my membership now. If you fancy joining, here’s the link.)

I genuinely enjoyed reading this. I didn’t know the story of English Heritage, so I loved the mention of the history behind the change and found the breakdown of the profit a nice touch. Well written and informative.

As a traveller, I have to say the UK has the best system when it comes to historic sites, and now I understand why. I love that museums are open to the public and run on donations. Usually when you visit places you budget yourself, but the UK makes it easy to see all your favourite sites, whether it’s through tourist bundles or visiting a museum (for free) when you’re in the area. Definitely appreciate the country’s involvement in making history accessible.

LikeLike

I’m glad you enjoyed it! I’m very pleased as a historian to see how much care the government put into the whole English Heritage project 🙂 it shows they actually appreciate how rare it is to have a preservation system that doesnt cost the govt any money. So many govts around the world don’t take good care of their heritage and it gets damaged or destroyed 😦

LikeLike